Originally published in Percussionist (Winter 1977), vol. 14, no. 2.

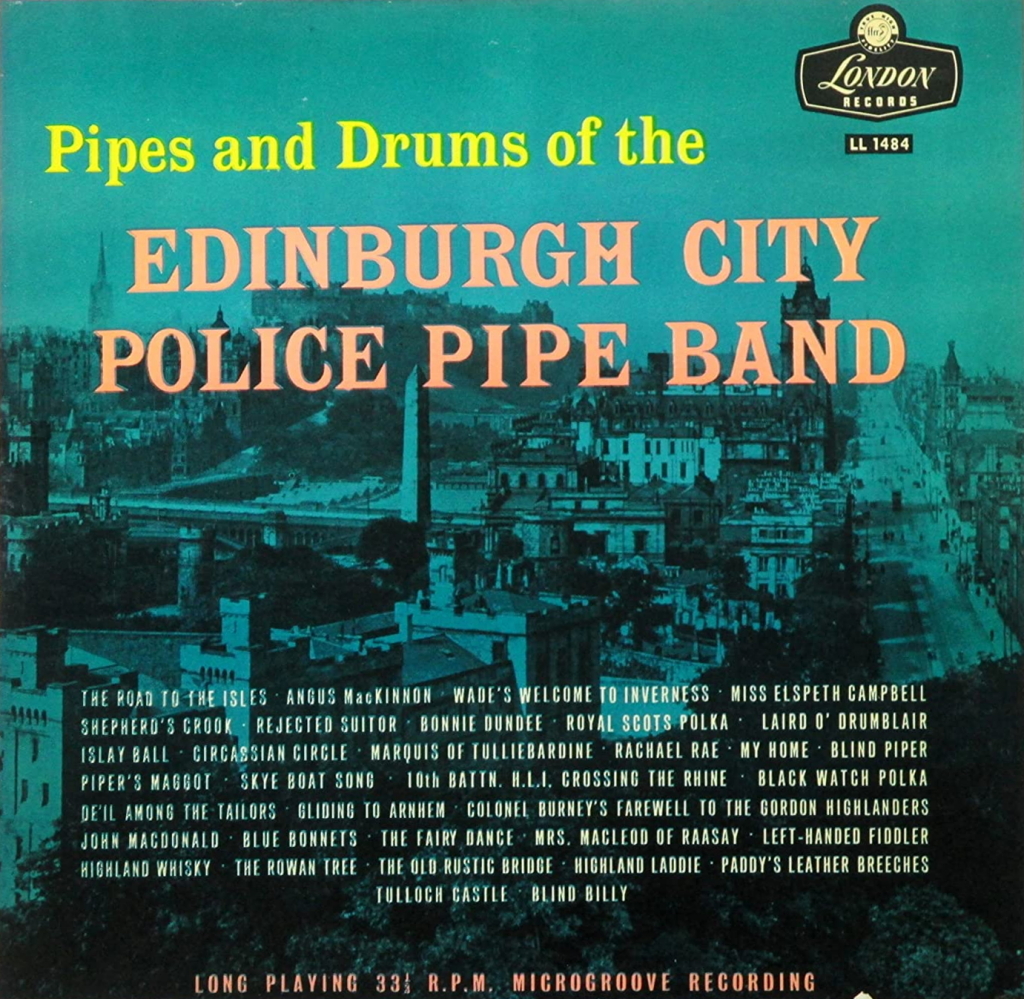

About the Author: Mr. Boag is assistant to the Keeper of the Scottish United Service Museum in Edinburgh Castle He has been a percussionist for over forty years and has performed with top Pipe and Drum Bands such as the Edinburgh Special Police Band Mr. Boag is also a leading orchestral percussionist, instructor and music historian.

Sometime during the years immediately following the Crimean War, an event took place which was to have the most surprising effect on the playing of street or marching drums. This was the employment together, for the first time, of bagpipes and drums by some Scottish regiments in the British Army. Probably inspired by the resounding success of the French “Field Music” and the authority, granted for the first time in 1854 for the official employment of pipers in the army, some enterprising Commanding Officer put his regimental pipers and regimental drummers on parade together. Despite its recent occurrence, it is not known who the enterprising officer was, nor which regiment was responsible. From this simple beginning, an entirely new style of side drumming technique was to evolve within 50 years, and within 100 years was to become a tradition in Scotland and was to make its mark world wide as being probably the most skillful and phenomenally difficult style of playing to be heard anywhere as a purely side drum technique.

It is said that for many years, the British army side drummers had been taught, not by music, but by rote and had learned their rhythms and beatings purely by ear. For this reason, not a great deal is known about the early styles of playing, but it is probable that these were closely akin to those used by the Fife and Drum Corps of Williamsburg and the NARD exponents. Bagpipe music had changed greatly during the 19th century and that time had seen the emergence of many marches, the first collection of which was published in the early 1800s. The very nature of this music, containing, as it does a multiplicity of grace notes, gives bagpipe tunes a characteristic all their own which is not easily described in words, but which can turn a simple melody into an extremely foot tapping, lilting series of extraordinary rhythmic patterns which are linked as much to the grace notes as to the basic rhythms of the melody. Indeed, a pipe tune played without its grace notes can be dull and repetitive rhythmically and yet, after the addition of the ornaments, can become excitingly different.

To suit the needs of this music, the drummers of the Scottish regiments had to think afresh about what they played. As with all marching music, these tunes were in 2/4, 4/4 and 6/8 meter with the odd 3/4 piece and most of them were in quick time. Because this art was new, no one was able to think beyond reapplying the existing techniques, to sit as comfortably as possible on the melodies, and it was rapidly realized that a simple basis of short rolls, paradiddles, flams and drags could be made to supply all that was required. In retrospect, it would appear that nobody in the drumming world had yet realized the potential of the opportunity provided by these grace notes, or that if they did see it, they did not know how to exploit it. In fairness, it must be remembered that the purpose and function of these early pipe bands was to provide a good basic rhythm to assist men to march and the public spectacle and display aspect had not even started to develop. Indeed it is necessary to leave the army at this point and look to the area in which the greatest innovation took place, namely, the civilian pipe bands, which began to make their appearance very shortly after the regimental pipe bands, and upon which they were and are modelled. As a pure digression, the question could be asked about how many people realize that when they call themselves pipe major or drum major or drum sergeant or whatever, they are using army appointment titles which have no meaning and no function outside the army.

There were certain civilian organizations with a disciplined structure, such as the Police which rapidly developed pipe bands, the earliest being probably in Govan (a suburb of Glasgow) in the 1860s. The highly elaborate dress of these bands was a “natural” for public spectacle and it is in them that the drumming style began to evolve. However, they were closely based on army bands and often contained ex-army pipers and drummers. The evolution was long and slow and was due principally to the arrival of Pipe Band Contests which became a feature of Highland Games. In those early days, before World War I, the bands were simply judged as bands with no specialization with pipes or drums, but following 1918, when the World Championships at Cowal Highland Games became a Mecca for bands, a few bold enthusiasts began to develope special techniques for the drums, by using accented strokes in unusual places and linking basic rudiments to give a new effect. There can be little doubt, that the emerging specialization of the percussion demands by modern classical composers and the rag-time and dance band scene had an influence.

Until the 1930s, the majority, if not all, pipe bands had rope-tensioned drums, which had a fine resonant sound, but relatively poor tension. In 1930, the Premier Drum Company produced a full depth, rod-tensioned side drum suitable for pipe band work and, it appears that one was sent, or loaned to Jack Seaton of Glasgow City Police Pipe Band. James Catherwood of the Dalziel Highland Pipe Band in Mother- well managed to convince his committee that they should purchase a full set of these drums. In 1931,at Cowal Highland Games, they won the World championship using them. This is the first recorded instance of a pipe band appearing with bass, tenor and side drums, all rod tensioned, all individually tensioned. Jimmy Catherwood told this author that they were laughed at by the traditionalists because of their “biscuit tins”. After playing and winning, the laugh was on their side and by the following year, all bands who could afford it, had reequipped with the new drums. The changes in style of playing which had been coming, suddenly erupted and the whole pipe band drumming movement leaped into the 2Oth century, except for the army and a large number of little local town bands who were not interested in, or capable of competing. For these players, the old tried and proven steady army beatings were good enough and truth to tell, there is still a dignity and cadence in these, which is effective and moving when played with a good sense of dynamics and style. Not one of these army beatings required more than the ability to play rolls, accented rolls, the paradiddle, flam, drag and the triplet, and the triplets were frequently used in such a way as to sound like a four-stroke ruff.

The civilian competitive bands however were using “big” tunes, i.e., tunes difficult for the pipers to play and on which the standard accepted simple beatings sat idle or not at all. This forced their drum sections to try other tactics which lead to innovations in composing rudiments, using accents, drag and flam paradiddles, 6,8, and 10-stroke rolls and the abandonment of the steady four in the bar accents of the Strathspeys, but rather writing special parts for individual tunes. The older beatings had simply been omnibus 2/4 or whatever rhythms could be used with any tune in a given meter signature. As these bands were not really marching bands in the army sense, they had more freedom to exploit unusual patterns and place accents and stresses in unusual positions all helping to “point” the melody for the pipers and therefore, approaching greater ensemble playing. Names began to appear in the drumming world of the pipe bands Jack Seaton of Glasgow City Police, Jimmy Catherwood of Dalziel Highland, Paddy Donovan of Fintan Lalor. All of these men made a contribution which can never be forgotten and despite being keen rivals, were also good friends who shared some, but not all of their secrets. This author has a little scrap of manuscript paper with an idea for using accented ruffs in Strathspeys, written by Paddy Donovan and across the top is enscribed “Not to be given to anybody”. It is now interesting for this author to realize that this was the forerunner of a much later development wherein open six-stroke rolls, preceded by an accented stroke, were used with telling effect in jigs. By the end of the 1930s, the pipe band drummers were using a wide variety of rudiments, linked together, played in unusual sequence, accented in the “wrong” places, and had already produced a style which was exclusive and specialized. By today’s standards, it was still fairly simple, but the seeds sown by the giants were sprouting and the harvest was ripening. During these years, those of us who were not fortunate enough to come under the tuition of the great men stood and marveled at the playing they did and the effects they achieved. It was also a period when we learned to use our eves as well as our ears, trying to see how they played their material by relating hand and stick action to the sound.

In 1939, the Second World War began, which delayed progress for a year or two because many of the men in the bands were called up for duty and naturally, activity was at a lower pitch. However, many of those called for service took their sticks and went into army bands and thus, introduced the first stirrings of modern techniques to that section of pipe bands.

After the cessation of hostilities, the activities of the Scottish Pipe Band Association took on a new lease of life and, starved of color and ceremony for years, a complete new generation of enthusiastic youngsters came into the movement and many new bands grew to join the ranks of the resuscitated and well-established top class bands. The majority of the competing bands, freed from the shortages and restrictions of the war, purchased new drums and the final days of the rope tensioned drum were numbered. New names appeared — Gordon jelly, Teddy Gilchrist, George Pryde, Alex Duthart, Frank Ross, James Blackley — all of these players were not only remarkable executants, but clever and inventive innovators who talked, lived and ate drumming. Prior to this time, the writing of drum parts for pipe bands had been a fairly hit and miss affair with as many ideas about the writing of certain things as there were drummers writing them. Now, however, these men got together and discussed notation, sticking and execution techniques and, with the experience of the older school, laid a new foundation for the structure. It is perhaps significant that none of these players had had any formal musical education and possibly this left them more free to explore and experiment.

The advent of the rod-tensioned drum had two important effects. The first was that the higher tension and higher pitch made it easier to play more advanced technical parts, but the counter effect was that a certain amount of volume was lost. The classical rudiments were looked at again and the use of open rudiments and the single-stroke roll came in with very telling effect. By now, late 1940s and early 1950s, the manufacturers had realized that there was a big market in the pipe band world and began to produce more improved drums in an attempt to give the players what they thought they required. Metal counter hoops had been used before 1939, in fact most drums of 1931 had them, but now, orchestral-type floating heads, wire and silk and wire snares were tried; and in attempts to push the pitch of the drum higher with greater snap and crispness to the playing, batter-head snares were introduced. Probably due to methods of manufacturing and greater production lines, these were fitted with snare releases like dance band drums and they brought their own problems. Dance band drums had never been designed to take the hammering that field drums received, nor were they designed to take the extremes of tension applied by the drummer; therefore, much work and research remained to solve these problems. Another development began to manifest itself in the 1950s. The enthusiasm for sheer technical brilliance by players began to run away with them, and by fitting rhythms into big, complicated tunes, they began to write material which supposedly fitted the melodies, but which, in fact, was frequently over complicated. This led to excesses where rolls became tighter and tighter, with as many strokes pushed into a measure as it was possible to get. The beatings became extremely elaborate, and in many cases, quite tasteless.

Jimmy Catherwood was not only an enthusiastic pipe band drummer, but a keen all-round percussion player, and for various reasons, and had met and been in correspondence with many international authorities on the subject. He had developed an interest in American Rudimental Drumming, and also in the highly distinctive and specialized Basler Drumming of which the late Dr. Fritz Berger was the leading exponent. It was largely due to this contact that many of the newer names in pipe band drumming were able to meet and hear Dr. Berger on his visit to Scotland shortly before his death. Some of his style rubbed off and was utilized by the Scots so that pipe band techniques, by the late 50s and early 60s had become an amalgam of traditional styles from many parts of the world. It is probably true to say that it was upon the Basle type of notation, that Alex Duthart based his method of writing parts for the pipe band — a single line stave with all strokes of the left hand notated above the line and right hand beneath.

A further change came about with the development of close and active cooperation between the leading exponents and the Premier Drum Company. Alex Duthart in particular, commented and advised on the shortcomings of the field drum as then produced. Research, largely of necessity and by trial and error, was attempted in an effort to produce a drum for pipe band purposes which had a brilliant, snapping tone, but which was not deficient in volume. There existed a serious problem for many years due to the snare mechanism, particularly for batterhead snares which never seemed to lie absolutely flat and evenly against the head. Additionally, it was difficult to get really accurate adjustment of these and, as a result, they often tended either to kill the tone, or to produce a nasty buzzing effect which destroyed the whole effect of the playing. The collaboration produced a very fine drum, suited exclusively to pipe band work in the field.

Sticks too, had presented a never-ending series of problems and fashions changed rapidly over the years as each band copied the type of sticks used by the most successful Grade I competitive bands. Danga, parrot, hickory, lancewood, mahogany, oak, laminated and a wide variety of materials were used. Acorns (beads) were large, then small, then almost non-existent, as attempts were made to produce a first class stick suitable for the type of playing needed. Eventually, Alex Duthart designed a stick which is most popular today, and which is vaguely reminiscent of the incredible sticks of the Basle school. These latter were long and heavy with a very thick shaft and an acorn about the size of a large grape. The Duthart stick is 413mm in length, completely tapered from butt to acorn. It has a large acorn and is about 24mm thick at the butt. Despite its clumsy appearance, this is a remarkably good stick — fast and clear. This author uses them for orchestral playing with great success. On the very highly tensioned pipe band drums they are lively and produce a first-class response.

A further change has been taking place over the past five years in the actual style of beatings. The Scottish drummers use generally what can best be described as a melodic style, being closely linked to the melody played by the pipers. As we have seen, this became elaborated and in an attempt to do something different with an already complex style, the 1950s saw the growing use of dynamics and “‘light and shade”. During these years, this author cried as a voice in the wilderness for a return to simpler styles, but with great dynamic control and lots of expression. This has, in fact, come to pass and today’s pipe band drummer is no longer guilty of “rivetting” techniques, but is a master of the ppp-fff. Material is still highly complex, but of simpler and better construction and played with great style. The future looks bright for this odd mixture, this hybrid style which is now recognized as being “purely Scottish”.

As an interesting final thought, it should indeed be pointed out that 99% of all civilian pipe bands in the world are 100% amateur players. There have been few professional pipe bands and these amateur drummers give up their nights and weekends to learn and to impart the skills of their art. Anyone in Scotland can learn this art provided he or she has a certain degree of ability, the enthusiasm to work hard and practice arduously. It will cost him or her very little, usually the shoe leather to walk from home to the rehearsal hall.

W. G. F. Boag